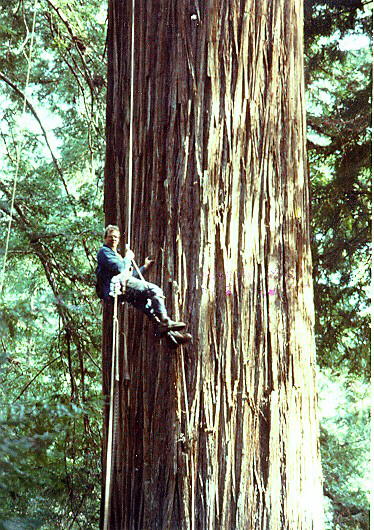

RALPH STEARNS DYER REDWOOD CLIMBMontgomery Woods, California

Link to pic of the Reynolds Triple Redwood in Mendocino County |

| Redwood Expedition Climb: The Big Tree

The alarm went off way before dawn. I woke up in strange surroundings, with a faint coastal breeze coming in the window. The day before, I had driven 400 miles from my home in Oregon to get to this part of Northern California where the tallest trees in the world grow. Now it was time to drive another hour in the pre-dawn darkness to the old growth grove of redwoods where we were to climb. I wanted a scenic spot to have lunch--a place with a nice view, and this trek with fellow Tree Climbers International member Jerry Beranek was just the ticket. It's not that I had never climbed a big tree--cone collection contracts in Oregon had included 200 foot Sugar Pine--but the challenge of the biggest of them all was somehow compelling and mysteriously unresistable. Jerry's reputation as a consummate master of the redwood empire was comforting enough to allay the fear of attempting something that most people regard as foolhardy. Leaving the perfectly safe ground to ascend over 300 feet in the canopy is, admittedly, very hazardous. By using the most modern climbing techniques, safety procedures, and proper equipment, we turned a lark into an expedition. Upon arrival at the site, we had to pack our gear in. This meant we couldn't bring much gear, period. The tree was about a quarter mile up a moderatly steep trail. (Another quarter mile farther is the 357' tree that was climbed by Jerry and TCI founder Peter Jenkins and detailed in the winter '87 issue of TREE CLIMBER magazine). Weather conditions were perfect--the day had dawned bright and clear--but as we entered the grove, the light level dropped to a deep twilight shade under the multi-level forest cover. No sky was visible to us down here on the forest floor, and the tops of the trees couldn't be seen either. We felt like mere ants in the land of the giants. My mouth gaped open in awe as the first few monstrous trees came into view. Only a couple hundred feet of their trunks were visible, giving the ominous impression that the trees were a staircase to Jack-in-the-Beanstalkville. We had entered another world--where time had stopped twenty centuries earlier. We scrambled over enormous rotten logs that had lain there, undisturbed, for 500 years (They must have been several thousand years old when they fell, soundlessly). We made the transition in our minds, as well. We were now with nature, not in it. It was quite obvious when we reached the tree. It was significantly larger than the others, fifteen feet in diameter, and very tubular. The sides of the tree trunk were parallel--there was no apparent taper as my eye travelled up the massive trunk. I craned my neck back and looked up and up, the limbless trunk vanishing overhead into the competing vegetation. Oh yes! This was indeed what I had come after. Jerry didn't waste any time preparing for the ascent--he knew what to do because he had been up this particular tree before, so he acted as the lead climber. The plan was to go up a smaller tree, swing over into a larger, twin-spired one, then transfer on over into Big Daddy. I put on my Euc Man buttstrap saddle and was starting to flake out the 175 foot Safety Blue climbing line, when he stopped me, saying that it should be carried coiled because it wouldn't be used until quite a bit later. I suddenly envied his lightweight 200 foot, three-eights inch Gold Line and hand braided saddle. Our philosophies varied widely in the gear department. Jerry is very minimalist, preferring to make his own, or adapt existing equipment to his specialized uses. Ascenders and line guns are some of the rigging tools he likes to use. As for me, I like to carry a truckload of conventional arborist equipment of the kind typically found in a Sierra Moreno Mercantile catalog. All aerialists have their own preferences--from professionals like Window Washers; Silo Painters; Ironworkers; Electrical Linemen or Tree Surgeons, to amateurs such as Spelunkers; some Search & Rescue people and Rock Climbers. Recreational tree climbing takes from all these disciplines and uses whatever works. The night before, Jerry had cut and spliced a special, 30 foot flip line for me. Now it was plain enough to see why. Also, we used climbing spurs, (not recommended by TCI), so we could confine the climb to a one-day event. Jerry cautioned me about nicking the top of the limbs, where breaking a small amount of tension wood can cause large limbs to fail. We put on our backpacks filled with camera gear, lunch, and other climbing stuff. Jerry ajusted his flipline around the smaller redwood (a seven-footer! ) and started walking up the tree. I followed. What a workout! My anticipation turned quickly to perspiration as I tried to keep up with Jerry, who moved smoothly upward, above me. It was important to take big steps, so the large diameter portion of the trunk didn't consume too much of a limited ration of energy. I felt like a fly climbing a flat glass wall. The bark was surprisingly firm, not like the spongy bark of the puny backyard redwoods I periodically climb as an arborist. The spurs barely penetrated. As we went up, I made sure to keep at least one limb between us as a safety precaution, lest he slip and come down against my flip line. A second flip line was used for security as we unhooked to vertically pass by limbs. My usual flip line is an eight foot length of proof coil chain, secured by Klein harness swivel snaps at a side dee ring. This arrangement makes for excellent adjustment of length, although somewhat heavy and noisy (Some people accuse me of having offended the Gods, and of being condemned to chain myself to the top of a tree every night, where an eagle tears out and consumes my liver! ). As we approached the two-foot diameter level, over a hundred and fifty feet in the air, we were at a bare spot in the canopy of the neighboring tree. This was the location where the first transfer would take place. Jerry paused and told me to wait while he went up about 50 more feet to get a good tie-in. He went on up, got tied in with a taught-line hitch, then slid back down to where I waited. There was plenty of pendulum in his line. He swung over to the next tree, whose limbs were about 15 feet away. He attached himself to the trunk with his flip line, then unclipped his climbing line and sent it back to me, where I repeated the procedure, and joined him. This twin-trunked tree was hollowed out and bare of limbs in the space between its two spires, like a big, outdoor room. Actually it was more like stepping into a huge empty cathedral, majestic with sparkling dust floating in long beams of filtered sunlight streaming down through the stained-glass foliage. The trunks were like massive pillars, and branches radiated out from the center. This ancient cathedral was more than twice as old as any built by man. We climbed another hundred feet in reverent silence. We bridged to the opposite of the tree, where the next transfer was to take place. This time it was my turn to go up to set the line. Since the distance to be traversed was greater this time, I went up a little higher, sixty to seventy feet, then came back down on the taught-line hitch. Jerry took the tail of my climbing line and tied a special 'Jam Knot', which he expertly tossed over to a spot on the big tree where two interfering limbs crossed each other. It wedged itself firmly between them, allowing me to hoist myself sideways, hand over hand, until gaining a good enough hold to flip my safety chain around a limb on the big tree and slack off the climbing line. Working my way sideways over to the trunk on some foot-in-diameter sized limbs, I went up the trunk a ways and got tied in with the tail of the rope. Going back down to Jerry's elevation, he threw me the tail of his rope, which I tied to the climbing line set in the big tree. He pulled it over to himself, and, suspended between the two trees, made his transfer. We were now all set to make the final leg of the climb. At this point, about 250 feet above the ground, the trunk was still six feet thick. It made the tree we had just come out of look like a scrawny sapling. There was a lot of limb-over activity, using two flip lines for safety as we climbed up. Jerry went to the top, pulled up my climbing line and got me tied off, so I could make the last part of the climb without having to keep stopping to flip in. Such a team effort saves a lot of energy, and is much safer than each climber replicating the movements of the other. Swapping gear as the situation demands results in a synergy unattainable by a single climber. When we finally reached the top, Jerry said, "Congratulations on breaking the 300 foot barrier! ". We didn't know exactly how high we were at the time, but I felt overjoyed and relieved. We had a chance to talk and relax after the grueling effort. There was plenty of room for us both in this flat-topped tree. The treetop was pancake shaped, with limbs the same diameter as the trunk fanning out at the top. Maybe gravity had decided that sap couldn't rise any higher than this. By standing on the top branch, my head was higher than any part of the tree, and I could see in all directions. Farther up the valley was a whole hillside of 300 plus footers. Old growth has the striking characteristic of showing large portions of individual tree trunks, as they extend well above the understory in a magnificent panorama. The ground was invisible, forgotten under a carpet of velvet green, far below. Besides, we had worked up a big appetite, so it was time for lunch. And what a view! All good things must end, and it was finally time to come down to earth. We had one thing to do on the way back down, which made the descent more exciting, and less of a chore. Jerry wanted to measure the exact height and diameter of the trunk. So, with one end of a fifty foot tape, he started lowering himself off the edge of this flat world into the abyss. I held the other end of the tape at the highest point of the tree. After he reached the fifty foot level, I decended to his level, where we measured the circumference. The tree was fifteen feet around, or five feet in diameter. Another fifty feet down, it was seven feet thick. Fifty feet below that it was nine feet thick. It started to become quite an operation for two climbers to maneuver the tape around this massive girth. With all the limbs, there was a lot of clambering around. When we reached the lowest limb on the tree, (which was about a hundred and sixty feet above the ground) we switched to single rope technique. Doubled, our ropes would not reach the ground. Jerry tied a running bowline around this limb with my half inch climbing line. He tied his climbing line through the bight of my bowline for later retrieval of the two ropes. We then continued our descent on figure-eight rappeling devices. We continued to measure girth every fifty feet. After the sixth measurement, or 300 feet, we were almost at ground level, and Jerry went down, leaving me up in the tree, holding the tape. He made the last measurement at ground level and announced that the tree was 336' 3" tall (There may be a little room for slop in this measurement). Here I am hanging on a hundred and forty feet of my rope with it footlocked off below the figure-eight decender. (Ever footlock with spurs? ). (Note: Footlocking is a very fast rope-climbing method where the rope is wrapped around one foot, then clamped down by stepping on it with the other.) Jerry decides to set up a tripod to take some pictures, since the light is so low. To keep my mind occupied, he takes the tail of my rope, and walks me all the way around the tree trunk about three times, says "Hang on! ", then throws me out into space. What a wild ride! I coiled around that maypole a half dozen times--with all the strech in the line it was a wide, springy arc, like a ride at Disneyland. When I came in for a soft landing, I pushed back off again and wrapped around three or four more times, until it was time to pose for the last picture, thirty-six feet off the ground. When I rappeled to the ground, it was definitly time to relieve my bladder, so I stepped over to a convenient bush. I heard a challenging voice say to Jerry, "Where's your commercial photography permit? ". Well, Jerry had mentioned that he had told some friends where we would be climbing that day, so I assumed it was them. Wrong! It was a resident park aide, who was apparently out of things to do at the moment. Since there is no procedure for dealing with errant tree-climbers in his guidebook, I guess he figured that he better invent one. At the time, I felt like turning around from the shrubbery and answering, "I've got your permit right here! ". But I finished up, and let him say his piece. He was concerned that falling limbs that we had dislodged could possibly injure hikers, since we were on state parkland. A valid issue, since we had no support from a ground party to secure the area (a major fault). After checking our ID, and some more posturing to demonstrate his authority, he went away. After some figuring on the calculator, Jerry computed the cubic volume of wood from our measurements of the tree. At the going market rate for clearheart redwood lumber, this tree would have brought more than a quarter of a million dollars at retail price. It's a good thing it's located in a park reserve, and is protected by law. I hope it stays that way. I'm still looking for my next fun climb up a monster tree, in Oregon, California, or anywhere. I've got my eye on the Big Pine (the worlds tallest Ponderosa Pine at 250 feet) near my home in Southwest Oregon. Or, maybe it'll be a tree in your neighborhood! |

Home |